Claire is the one who instigated the affair, and yet she calls herself a victim. She is a completely selfish woman, as demonstrated by the fact that she wanted to wreck one of the most successful marriages she had ever seen.

Anything that is seen as beautiful is immediately suspect. The end of the novel de-reifies beauty...Zadie Smith hates the objectifying of women, but she wants to be able to talk about beauty. Howard, for example, claims to be above the idea of turning art into beautiful objects, but as soon as some good-looking women "seduce" him, he immediately sleeps with them. This presents itself as a HUGE contradiction.

Meanwhile...Zora has been working to keep Carl in her poetry class, because Monty has been trying to get the non-paying, "unqaulified" students kicked out of the program. Monty, however, has been sleeping with one of those students, and wants her kicked out so that he can cover up for what he is doing. At the party, Zora, Jerome, Victoria, and Carl are all confronting one another. Carl alludes to the fact that Howard slept with Victoria, and tells them outright that Monty has been sleeping with Chantelle. Jerome understands what Carl doesn't say, but Zora is too concerned with the Carl/Victoria situation to make sense of the allusion. Carl, surrounded by all these liars, sees the academic life as full of smoke and mirrors. He is tired of being a "plaything" for radical intellectuals: "You got your college degrees, but you don't even live right. You people are all the same" (418-419). Consequently, after this party, Carl never comes back to Wellington...he has seen the intelletual world for what it is, and wants nothing to do with it.

Racial issues also come into play towards the end of the novel, during the confrontation between Levi and Kiki. Levi has stolen Mrs. Kipps's painting and Kiki finds it hidden under his bed. She and Levi thus get into an argument about who the painting has been stolen from--Levi insists that the money from the painting should be redistributed, and Kiki repeatedly tells her son that he should never steal, bottom line. Levi also blames him mother for "selling-out" by marrying a white man, and paying her Haitian maid only four dollars an hour.

By the last two pages of the novel, Howard is in a downward spiral...Kiki knows about Victoria and she has moved out. The children don't tell Howard where Kiki is living, and he lives with the kids in the Welligton house. They despise him, and yet they still talk to him--miraculous. In the very last scene, he is giving a speech in Boston, trying to get hired at Harvard. When he looks out in the audience, Kiki is there. He makes eye contact with her, and she smies...

BLOG ABOUT BEAUTY On these last two pages

Friday, April 24, 2009

Wednesday, April 22, 2009

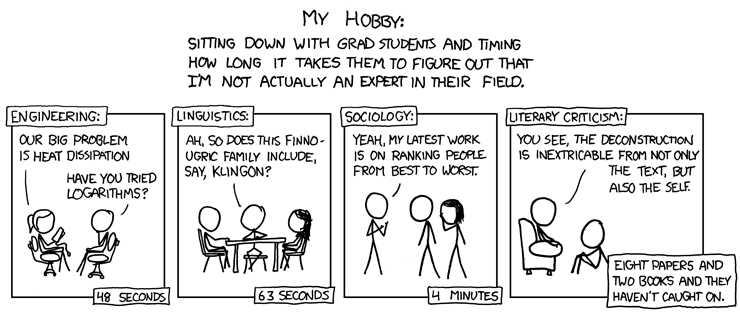

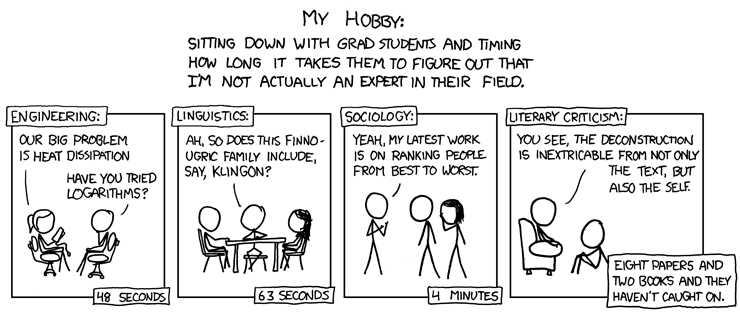

Literary Theory: An Introduction

Literary theory encompasses the varying ways to read and make meaning of a text. From the 1920s to 1950s, there was the idea of "New Criticism." It was a way of seeking out contradictions in a text and figuring out how those contradictions unified the text and created meaning. These contradictions are there for a reason, and create meaning rather than canceling each other out. In this way of thinking, you look at just the text itself, centered around what the author meant. With the evolution of literary theory, this notion on authorial intent loses its importance. In the 1960s, there are cultural revolutions in America, England, and France. A lot of the ideas carried over into the study of English literature. Some of these ideas included psychoanalysis and studies of the unconscious. Such Freudian views are supposed to direct our thoughts and actions so that we understand the latent contents of dreams (books) in order to understands ourselves(books). This idea developed into the Psychoanalytic theory of literature. A similar thing happened with Feminist theory, in which we read texts to discover hidden (or not hidden) meanings about female desire, empowerment, equality, sexuality, gender politics, and POWER. Queer theory also develops, focusing upon gender issues, power, hetero-normative ways of thinking, etc. Basically, Queer theory asks 'How is queer identity constructed in a text?' Deconstruction is a theory that came about in the 1970s. It maintains that there are a lot of privileged oppositions in the world, and that speech is always privileged over writing. Accordingly, we privilege the faculty of reason over all else. Historically (in the West) reason has been used to judge what makes a human a human. Thus, we are logocentric-- historically, Westerners have judged "others" as lacking the faculty of reason, privileging out culture over others'. Beyond this, the work of deconstruction looks to question these ideas of opposition and privilege. It is a way of questioning how language discloses meaning.

Literary theories thus quickly become charged with political meaning. This is really the beginning of the Academy as a political space; it has come a long way from New Criticism. Such ideas come up against a lot of criticism for those who say that we should not be looking for such political elements within texts. We are now looking for cultural significance rather than the intentions of the author. Within the larger picture, each text has a cultural meaning. Texts are now seen has having larger social significance, and we cannot analyze them without analyzing the culture as well.

Literary theories thus quickly become charged with political meaning. This is really the beginning of the Academy as a political space; it has come a long way from New Criticism. Such ideas come up against a lot of criticism for those who say that we should not be looking for such political elements within texts. We are now looking for cultural significance rather than the intentions of the author. Within the larger picture, each text has a cultural meaning. Texts are now seen has having larger social significance, and we cannot analyze them without analyzing the culture as well.

The definition of "text" also emerges and expands. Text is now thought of as including poems, novels, plays, films, television, digital images, art, CD's, music, clothing, graffiti, advertising, etc. A text is a thus a cultural artifact and can be interpreted in some way. This also causes trouble because we are dealing with so many different texts that can be brought into the classroom and studied. Thus, the classroom becomes highly politicized. Conservatives do not want all this "stuff" contaminating the "real art/text" of the academy.

Common to all these theories are ideas of power, subjectivity, political significance, cultural significance, and types of representation. With so many different theories, we are able to analyze texts from a variety of perspectives.

Literary theories thus quickly become charged with political meaning. This is really the beginning of the Academy as a political space; it has come a long way from New Criticism. Such ideas come up against a lot of criticism for those who say that we should not be looking for such political elements within texts. We are now looking for cultural significance rather than the intentions of the author. Within the larger picture, each text has a cultural meaning. Texts are now seen has having larger social significance, and we cannot analyze them without analyzing the culture as well.

Literary theories thus quickly become charged with political meaning. This is really the beginning of the Academy as a political space; it has come a long way from New Criticism. Such ideas come up against a lot of criticism for those who say that we should not be looking for such political elements within texts. We are now looking for cultural significance rather than the intentions of the author. Within the larger picture, each text has a cultural meaning. Texts are now seen has having larger social significance, and we cannot analyze them without analyzing the culture as well.The definition of "text" also emerges and expands. Text is now thought of as including poems, novels, plays, films, television, digital images, art, CD's, music, clothing, graffiti, advertising, etc. A text is a thus a cultural artifact and can be interpreted in some way. This also causes trouble because we are dealing with so many different texts that can be brought into the classroom and studied. Thus, the classroom becomes highly politicized. Conservatives do not want all this "stuff" contaminating the "real art/text" of the academy.

Common to all these theories are ideas of power, subjectivity, political significance, cultural significance, and types of representation. With so many different theories, we are able to analyze texts from a variety of perspectives.

Tuesday, April 21, 2009

On Beauty, 4/17 and 4/20

On Friday, we discussed the nature of the culture wars--how they started and where they are today. Since they began in the 1960s (roughly speaking) the culture wars have moved to being centered among universities and intellectuals. We also discussed the differences between Kiki and Claire--and the importance of these differences in relation to the infidelity of Howard. Claire, unlike Kiki, is an intellectual like Howard. Perhaps he was attracted to this "sameness" he saw in Claire that is absent from Kiki.

On Monday, much of our discussion was focused upon Claire's poem, "On Beauty." The opening lines of the poem brings up the issue of pronoun identification:

Ideas of difference between the "beautiful" and the "ugly" also appear in the argument between Howard and Kiki that occurs on pages 206-207. After Kiki tells Howard that she staked her life on him, she goes on to accuse him finding someone (Claire) who is the complete opposite of herself. Claire, as a tiny, white professor, is physically and intellectually different from Kiki. Clearly, this makes a huge impact upon Kiki's self-image, and leads her to reiterate the claim that she staked her life on Howard.

Finally, we discussed the idea of role reversals within the novel. After Kiki talks to Carlene, she realizes that perhaps she has been living for Howard, not with him. This goes against the supposed marital views held by the Belseys, in which the husband and wife are supposed to work together, not for one another. There will probably be more role reversals as the novel continues--Howard doesn't even seem to believe what he is teaching anymore...

As we continue the novel, we are going to see whether or not the characters defy any societal expectations.

On Monday, much of our discussion was focused upon Claire's poem, "On Beauty." The opening lines of the poem brings up the issue of pronoun identification:

"No, we could not itemize the listThe pronouns of the poem are not specific, so we are unsure as to whether the beautiful or the ugly people are the ones itemizing the list of sins. Perhaps this inability to distinguish between these two groups of people alludes to the idea that we cannot just draw a dividing line between beautiful people and ugly people. The two may be separated in our perceived rendering of society, but in reality the divisions are not so clear.

of sins they can't forgive us.

The beautiful don't lack the wound.

It is always beginning to snow."

Ideas of difference between the "beautiful" and the "ugly" also appear in the argument between Howard and Kiki that occurs on pages 206-207. After Kiki tells Howard that she staked her life on him, she goes on to accuse him finding someone (Claire) who is the complete opposite of herself. Claire, as a tiny, white professor, is physically and intellectually different from Kiki. Clearly, this makes a huge impact upon Kiki's self-image, and leads her to reiterate the claim that she staked her life on Howard.

Finally, we discussed the idea of role reversals within the novel. After Kiki talks to Carlene, she realizes that perhaps she has been living for Howard, not with him. This goes against the supposed marital views held by the Belseys, in which the husband and wife are supposed to work together, not for one another. There will probably be more role reversals as the novel continues--Howard doesn't even seem to believe what he is teaching anymore...

As we continue the novel, we are going to see whether or not the characters defy any societal expectations.

Wednesday, April 15, 2009

On Beauty 4/15

Investigating the Left

In this book, we are given a bleak look of the left. Zadie Smith is, in fact, lionized by the left. In reading her novel, we get the feeling that perhaps she is anti-left. In the scene where Howard is talking to the curators of the museum, he is very snooty and sees them as being quite beneath him.

"To misstate, or merely understate, the relation of the universities to beauty is one kind of error that can be made. A university is among the precious things that can be destroyed." --Elaine Scarry

This quote is at the beginning of the chapter "the anatomy lesson." In this chapter, Zora threatens the Dean into letting her into Claire's creative writing class. In this instance, then, the university is not something that defends beauty. Does the accrediting of grades get in the way of finding and defending grades? YES. The university, then, is not really a defender of beauty. In the conversation between Zora and Carl, the topic of college education comes up. He tells Zora that by going to classes, she is just paying to talk to people about her ideas. Although Carl doesn't have a college education, he produces poetry for the sake of its beauty--not for the grades he could receive for it. Zora is pursuing a spot in Claire's creative writing class because it will look good on her transcript, and will help her get into graduate school. Carl, however, is a bit unusual in his pursuit of knowledge and experience.

Howard is living in a way that makes him feel dead. Perhaps his work life (as well as his romantic life) was dead. He tells his students that "beauty is a mask that power wears." Art, according to Howard, is a Western myth. As we keep reading, we learn that Howard is saying these things for the sixth year in a row. He might not even believe these "memorized" viewpoints anymore...

In this book, we are given a bleak look of the left. Zadie Smith is, in fact, lionized by the left. In reading her novel, we get the feeling that perhaps she is anti-left. In the scene where Howard is talking to the curators of the museum, he is very snooty and sees them as being quite beneath him.

"To misstate, or merely understate, the relation of the universities to beauty is one kind of error that can be made. A university is among the precious things that can be destroyed." --Elaine Scarry

This quote is at the beginning of the chapter "the anatomy lesson." In this chapter, Zora threatens the Dean into letting her into Claire's creative writing class. In this instance, then, the university is not something that defends beauty. Does the accrediting of grades get in the way of finding and defending grades? YES. The university, then, is not really a defender of beauty. In the conversation between Zora and Carl, the topic of college education comes up. He tells Zora that by going to classes, she is just paying to talk to people about her ideas. Although Carl doesn't have a college education, he produces poetry for the sake of its beauty--not for the grades he could receive for it. Zora is pursuing a spot in Claire's creative writing class because it will look good on her transcript, and will help her get into graduate school. Carl, however, is a bit unusual in his pursuit of knowledge and experience.

Howard is living in a way that makes him feel dead. Perhaps his work life (as well as his romantic life) was dead. He tells his students that "beauty is a mask that power wears." Art, according to Howard, is a Western myth. As we keep reading, we learn that Howard is saying these things for the sixth year in a row. He might not even believe these "memorized" viewpoints anymore...

Tuesday, April 14, 2009

Defining Beauty

Define "beauty" from Smith's perspective. Do you agree?

According to Smith, beauty is something that is constantly changing. The continual changes in our definitions of beauty depend on varying viewpoints, the current cultural standards, and our emotional ties to the thing we are (or are not) describing as beautiful. Howard, for example, finds Kiki beautiful not only because of her young face, but also because he knows that face, and finds beauty in the familiarity and memories associated with him. He finds beauty in Claire because of her tiny, "yogic" body, and perhaps even in the sheer difference between her body and Kiki's body. Clearly, the perception of beauty is constantly changing. There can never be one, authoritative definition of beauty. But as much as beauty changes with our own personal perceptions, it is impossible to ignore the fact that many of these perceptions are not self-created--rather, society plays a large role in creating them for us.

According to Smith, beauty is something that is constantly changing. The continual changes in our definitions of beauty depend on varying viewpoints, the current cultural standards, and our emotional ties to the thing we are (or are not) describing as beautiful. Howard, for example, finds Kiki beautiful not only because of her young face, but also because he knows that face, and finds beauty in the familiarity and memories associated with him. He finds beauty in Claire because of her tiny, "yogic" body, and perhaps even in the sheer difference between her body and Kiki's body. Clearly, the perception of beauty is constantly changing. There can never be one, authoritative definition of beauty. But as much as beauty changes with our own personal perceptions, it is impossible to ignore the fact that many of these perceptions are not self-created--rather, society plays a large role in creating them for us.

Monday, April 13, 2009

Notes, On Beauty 4/13

People we love may turn into objects for us, like the albatross in "Rime of the Ancient Mariner." There is thus an extent to which we objectify others, particularly those who are close to us. The notion of beauty has been impoverished in our culture, and we objectify the "beauty" that we see. In reality, (non-objectified) beauty is about lines and juxtapositions and contours.

To what extent is there a battle between non-objectified beauty and the conventional definition of beauty within On Beauty?

Zora thinks of her mother as "having let herself go" once she got married. Howard claims that he married a slim, black woman, and that Kiki is no longer that woman. He even goes so far as to say that physicality played a role in his affair. Carlene also comments on Kiki's weight, but tells her that she "carries her weight well" and that it "looks very well on her." Later, Carlene tells Kiki that she is beautiful. If you look at Kiki without objectifying her, she is a beautiful woman.

Claire's body is also objectified. She is constantly being described as petite, thin, and much much

smaller than Kiki. When Claire takes her students to the Bus Stop, she does what she has done her entire life, and orders a salad for dinner. Clearly, the idea of starving oneself is linked to Claire's tiny figure. At the anniversary party, Howard sees Claire for the first time in a year. She is described as tan, and youthful with a thin, yogic body. When Howard is watching her, he can't stop thinking about her body, how it moves, and what she looks like underneath her clothes. In the scene where Howard and Claire interact, it is clear that he values her intellectual ability--something which Kiki lacks and for which Howard continually makes fun of her. Claire tells Kiki that she should be in a fountain in Rome; this is not really a compliment, because the ideal Roman woman is full-figured and in contrast to contemporary (thin) notions of beauty.

Howard is a parody machine--he makes fun of "high" art, he makes fun of Kiki, and he argues against the notion of genius. When they go to see Mozart, Howard makes snide comments about the composer and the Requiem, saying that he prefers music that doesn't "try to fake him into some metaphysical idea" (72). Carl is listening to this conversation, and wants to tell the family that Mozart died before it was finished, and that someone else completed it. This thus redefines the notion of genius, adding a component of collaboration to it. The idea of the genius is even further defined by its constant gendering.

p. 207 Howard and Kiki argument

Wednesday, April 8, 2009

On Beauty

Zadie Smith on Art

Zadie Smith on ArtIn an interview Zadie Smith says that writers should not "hit their readers over the head" with their morals. The artist doesn't have to be a moral person, but a good work of art is honest and truthful in the artist's perception of the world. Because of self-deception, this is really difficult to convey in art--just as it is really difficult to comprehend in life. When writers berate you with their ideas, you feel as if you can't trust them. Instead, "good" artists will open a range of possibilities for the reader in order for the reader to see each and every side of the picture.

This is particularly relevant in the On Beauty because it deals with "The Culture Wars." On the right side, it is argued that students should study only the "greats" of the known canon. On the left side, it is argued that students should study multi-cultural works that do not necessarily fall into the category of "the greats" because all work can be seen as great.

Zadie Smith vs. 'Zadie Smith'

There is a difference between the real author and the person who has become an idolized bard. The left has done what the right does in tauting her as a "great" author. The 'me vs. them' has turned into an 'us vs. them.' So what is they right way to think about genius? If this book is "good art" it will offer multiple answers to this question, with multi-faceted characters on all sides of this argument. Delving into these deep characters offers an analogy for moral behavior in real life, and how we should develop real relationships.

In the novel...

Jerome is the bridge between his family (on the left) and the Kipps (on the right). The Belseys are Jerome's family, and they live in Wellington, Massachusetts. The mother(Kiki) and father(Howard) are fairly loose in their rules with children. The Kippses live in England and are a much more conservative family. They are pro-family, pro-busniess, and are practicing Christians. There is a rivalry between Monty Kipps and Howard Belsey. They are both professors of Renaissance art, and are both writing books about Rembrandt. Monty's book will hit the bestseller list, while Howard's book is still strewn about his study. Howard is searching for a way to prove that Rembrandt wasn't a great artist, while we can assume that Monty is working to prove the opposite. Jerome left to work for Monty over the summer. Perhaps he did it to get his father's attention, or perhaps he really wanted to learn a counter-idealogy to the one under which he has been brought up. Maybe he wants to get back at his father for having an affair; or maybe he's just constitionally different from the rest of his family. (People are their own people, after all). Either way, when Jerome comes back from England, he realizes that he has fallen in love with the Kipps family.

Sunday, April 5, 2009

Maria, or the Wrongs of Woman

Monday 4/6

Monday 4/6I liked the novella Wrongs of Woman more than the Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Although the ideas put forward in the Rights of Woman are all well-stated and interesting, the reading is just a bit dry. Wrongs of Woman, however, was much more of a "page-turner" as I found myself wanting to know what would happen to Maria. Now, superficially, it may seem that just because the Wrongs of Woman is easier to read, its words also carry less meaning. I definitely found that this was not the case. When reading a novella (instead of a proclamation of a treatise) you just have to look beyond the plot-oriented words and find the deeper meaning. This was true of Wrongs of Woman. In the novel's ending, for example, one is left to contemplate whether the individual desire for suicide is justified and more important than the necessity of staying alive to take care of one's children. If this were a proclamation, the "right" answer would simply be declared.

Thursday, April 2, 2009

Art and Lies: Romance

homework for Friday, 4/3

Do a close reading of a particular passage in Art and Lies: what question does it stimulate you to ask? What does it answer?

First Section of "Handel" pages 14-15:

If we don't desire romance, we are made to feel like something is wrong with us, like some significant part of us is missing. I think this ties in with our previous discussions about the pressure to lead a fairy tale kind of life. Romance is the ultimate goal; if you are involved in some sort of romance, you aren't just supposed to wish for one--you must pine for one. And if you simply don't think about romance at all, you are not a part of society. And this is not just a Western idea. In Japan, for example, the annual Tanabata Festival involves tying paper slips to trees that contain wishes for the fulfillment of romances.

Clearly, Handel is aware of this distinction between himself and the lady selling roses. He can perceive the disdain that the lady feels for him, and he understands the mystery he presents to his colleagues. But Handel truly isn't interested in romance. While at first it may seem as if this is a sad, pitiable quality within person, it retains a sense of respectability. Handel doesn't understand the feelings associated with romance; thus, he does not want to falsely sink into something just for the sake of being a part of society. He knows there must be more to romance than everyone believes there to be; he knows he is missing something, but unsure of what it is. And at least he possesses enough self-awareness to understand that since he knows what romance is not, he should wait to discover what it is before jumping in.

This seems to be cautious on Handel's part, and he does strike as a cautious sort of man. But perhaps his ideas hold some validity--before we simply follow the rest of the flock, we should stop and evaluate: do we understand what we're following? Does it make sense? Perhaps we should be like Handel, and instead of deciding to follow, we should wait until we are ready to lead.

Do a close reading of a particular passage in Art and Lies: what question does it stimulate you to ask? What does it answer?

First Section of "Handel" pages 14-15:

I was standing at the station, waiting for the train, when a woman approached me, with a wilting red rose in a plastic wrapper.What is romance? Why are me made to feel like we need it?

'Buy it for your lucky day.'

'When will that be?'

'The day you fall in love. I see romance for you. A tall blonde lady.'

'Romance does not interest me.'

She stared at me as though I had uttered a blasphemy in church, and I suppose we were in a church of a kind, the portable temple of sentimentality that can be flapping about your head at a moment's notice...My colleagues think me a remote sort of man, but, if I do not know what feeling is, at least I have not yet settled down into what I know it is not.

If we don't desire romance, we are made to feel like something is wrong with us, like some significant part of us is missing. I think this ties in with our previous discussions about the pressure to lead a fairy tale kind of life. Romance is the ultimate goal; if you are involved in some sort of romance, you aren't just supposed to wish for one--you must pine for one. And if you simply don't think about romance at all, you are not a part of society. And this is not just a Western idea. In Japan, for example, the annual Tanabata Festival involves tying paper slips to trees that contain wishes for the fulfillment of romances.

Clearly, Handel is aware of this distinction between himself and the lady selling roses. He can perceive the disdain that the lady feels for him, and he understands the mystery he presents to his colleagues. But Handel truly isn't interested in romance. While at first it may seem as if this is a sad, pitiable quality within person, it retains a sense of respectability. Handel doesn't understand the feelings associated with romance; thus, he does not want to falsely sink into something just for the sake of being a part of society. He knows there must be more to romance than everyone believes there to be; he knows he is missing something, but unsure of what it is. And at least he possesses enough self-awareness to understand that since he knows what romance is not, he should wait to discover what it is before jumping in.

This seems to be cautious on Handel's part, and he does strike as a cautious sort of man. But perhaps his ideas hold some validity--before we simply follow the rest of the flock, we should stop and evaluate: do we understand what we're following? Does it make sense? Perhaps we should be like Handel, and instead of deciding to follow, we should wait until we are ready to lead.

Monday, March 30, 2009

"Great Art"

Notes 3/30 Laura Mandell's theory of literary art:

The novel emerged in the 18th century, and the short story came into existence in about 1800. With these developments, genre fiction (which is formulaic) came into being.Certain genres of fiction and certain genre fiction writers have been included in the literary canon, while others have been excluded. Theoretically, the canon has now been blown apart. The study of "great" literature has been replaced with cultural studies. Some cultural studies proponents want to abandon the concept of "great art." Aside from the fact that this wouldn't work, it is not a good idea; we are all artists, and should all respect each other as such. However, when we think we find out what great art is, we project ourselves onto that art, giving credit to these artists and not to ourselves. In the "Stand By Me" video we watched on YouTube, it was easy to view all the musicians as great artists, despite the fact that they were "ordinary" people.

So why is it so hard for us to recognize the artists within ourselves, and within the "ordinary" people around us? Part of the reason is that we have a finite amount of attention that we have to give as well as a limited amount of attention that we receive. Perhaps from now on (at least for the rest of the semester) we should try to see everything as great art. If we don't love it and understand it, we should identify the fault as being within ourselves. Maybe we just need to learn more, to understand more, to become more open.

Thursday, March 26, 2009

Digitizing Text: "Child and Flowers"

Homework for 3/27

Go to poetess archive

Look at three versions of Bijon poem (child and flowers): page image, HTML version, TEI encoded version

Answer these questions:

Is the poem the same in these 3 versions?

Although the words remained unaltered, I found each version of "Child and Flowers" to be slightly different. Reading the HTML version was much like reading any old page on the web, and it simply felt different from reading an actual, tangible text. I really didn't have a sense for the authenticity of the poem. This feeling was further extended by my reading of the poem in the TEI encoded version. If i had ever stumbled upon such a format in the past, I simply would have dismissed it on the grounds that there must be some sort of technological error of transfer--much like when I try to open a document in Word and it ends up looking like a strange, unintelligible code. Once I got used to the format, I found that I could simply ignore the surrounding (and to me, meaningless) text. I think that the final version, the page image, was my favorite way to read the text. It felt more like reading an actual book, and I could more greatly appreciate the poem for its textual genuineness. Thus, the differences between these versions came not from the differences in text, but rather from the sentiments associated with each respective version.

What difference will digitzing make to our understanding of poems?

Digitizing poems allows the texts to be more easily accessible to a greater number of people. As we learned with programs like JUXTA and TagCrowd, the digitization of texts provides new and expanded ways of conducting research, leading to fresh perpectives and offbeat theories. Digitizing texts also gives them an aura of permanence that we have come to both expect and reply upon in an increasingly digitized world.

Apply the poem's theme about art to the poem itself: does digitizing contribute to Heman's aim in writing the poem?

I think that Heman's aim in writing the poem is to both create and preserve a piece of art. Digitizing, then, contributes to Heman's aim because it lends a sense of immortality to the poem itself.

In Class, 3/27

| "For a day is coming to quell the tone |

| That rings in thy laughter, thou joyous one! |

| And to dim thy brow with a touch of care. |

| Under the gloss of its clustering hair; |

| And to tame the flash of thy cloudless eyes |

| Into the stillness of autumn skies; |

| And to teach thee that grief hath her needful part, |

| Midst the hidden things of each human heart!" (lines 33-40) |

In this passage, the speaker is describing the time when a child will lose her innocence, when her eyes will be opened to the sorrows of the world. The speaker sees children as being capable of making incredible, untainted observations of the natural world around them. Th

e speaker, however, is idealizing childhood and its perceived air of innocence, not taking into account the fact that children are not always the happy, carefree individuals that adults believe them to be.

e speaker, however, is idealizing childhood and its perceived air of innocence, not taking into account the fact that children are not always the happy, carefree individuals that adults believe them to be.In class discussion:

The format does not necessarily change the meaning of the text, but it takes away from the reader's ability to process the poem and find its significance. The TEI version, for example, was so full of codes and symbols that I was too distracted to really read the poem. The important aspect of the TEI format is the surrounding code; a simple reading of the poem would be easier (and more logical) to do in the HTML or Page Image version.

These formats come into being in various ways. The "technology" of the printed book is so commonplace to us that we simply overlook it. It is extremely expensive to put page images online, but they offer the best representation of the original text. The HTML or Text versions, for example, often misplace stanza breaks or add strange characters. Even so, digitizing texts preserves them in a way that books cannot.

Monday, March 23, 2009

Digital Texts 3/23

1.Creating Tag Clouds for three versions of Frankenstein in small groups:

I created a Tag Cloud for the 1818 edition. The key words in my Cloud were friend, friendship, interest, noble, overcome, desire, creature, believed, and confidence. This edition and the Thomas edition are more similar, sharing key words like "friend" and "friendship." The 1831 edition, however, has darker words, including words like "dark" and "despair." The emphasis upon these words shows a greater concern for human emotion and the misery that consumes Victor.

Comparing these clouds helped me to understand the textual differences between the three versions, clearly illuminating the frequency of certain words. I was thus able to see the progression from the 1818 edition to the Thomas edition to the 1831 edition, as the text moved to incorporate more words about the human condition, particularly in relation to emotions.

Tag Cloud (1818 edition)

admiration although appears art astonishing believed confidence creature desire destroyed edition flow friend friendship history hope interest leaves letter life lost manner mentioned misery noble offended overcome pass pedantry plan pleased possible powers related respecting several speaks stranger succeeded suggested sun therefore tries true trust unsocial utterly watching wise wish

Did Mary Shelley write three different novels?

No, I do not think that Shelley wrote three different novels. I believe that each version was an expansion upon the previous one, adding new ideas and dissolving ones she no longer found important.

In these passages, the stranger agrees to different things. Why do those changes matter?

In the 1818 version, the stranger agrees that friendship is desirable and possible. Since he once had a friend, he is fit to make such judgments. He also says that since he has lost everything, he has no hope and cannot begin life anew. In the Thomas edition, the stranger agrees to the same thing, that friendship is desirable and attainable. In the 1831 edition, however, the stranger agrees that we are only "half made up" and that a friend ought to be our better half. Without such a friend, he says, we will remain weak and imperfect. These changes matter because they expound upon Victor's ideas about human nature. They show us his transformation into an extremely contemplative person, a person who understands the importance of relationships.

How does digitizing these texts help us think about these versions? How does it help?

Digitizing texts helps us to visualize them in a new and different way. This allows us to formulate fresh ideas about texts we have previously read, providing new insights. Essentially, digitzing texts is just another way of reinvigorating them.

I created a Tag Cloud for the 1818 edition. The key words in my Cloud were friend, friendship, interest, noble, overcome, desire, creature, believed, and confidence. This edition and the Thomas edition are more similar, sharing key words like "friend" and "friendship." The 1831 edition, however, has darker words, including words like "dark" and "despair." The emphasis upon these words shows a greater concern for human emotion and the misery that consumes Victor.

Comparing these clouds helped me to understand the textual differences between the three versions, clearly illuminating the frequency of certain words. I was thus able to see the progression from the 1818 edition to the Thomas edition to the 1831 edition, as the text moved to incorporate more words about the human condition, particularly in relation to emotions.

Tag Cloud (1818 edition)

admiration although appears art astonishing believed confidence creature desire destroyed edition flow friend friendship history hope interest leaves letter life lost manner mentioned misery noble offended overcome pass pedantry plan pleased possible powers related respecting several speaks stranger succeeded suggested sun therefore tries true trust unsocial utterly watching wise wish

Did Mary Shelley write three different novels?

No, I do not think that Shelley wrote three different novels. I believe that each version was an expansion upon the previous one, adding new ideas and dissolving ones she no longer found important.

In these passages, the stranger agrees to different things. Why do those changes matter?

In the 1818 version, the stranger agrees that friendship is desirable and possible. Since he once had a friend, he is fit to make such judgments. He also says that since he has lost everything, he has no hope and cannot begin life anew. In the Thomas edition, the stranger agrees to the same thing, that friendship is desirable and attainable. In the 1831 edition, however, the stranger agrees that we are only "half made up" and that a friend ought to be our better half. Without such a friend, he says, we will remain weak and imperfect. These changes matter because they expound upon Victor's ideas about human nature. They show us his transformation into an extremely contemplative person, a person who understands the importance of relationships.

How does digitizing these texts help us think about these versions? How does it help?

Digitizing texts helps us to visualize them in a new and different way. This allows us to formulate fresh ideas about texts we have previously read, providing new insights. Essentially, digitzing texts is just another way of reinvigorating them.

Friday, March 20, 2009

Aurora Leigh, Book V

Can there be heroes in modern life? According to the poem? and to you?

According to Aurora Leigh, heroes most definitely exist within modern life. She writes "All actual heroes are essential men/And all men possible heroes" (151-152). Clearly, AL believes in the heroic potential of every individual. In order to find such heroes, AL encourages not to look to the past, but to be mindful of the present. If we depend upon the past for our heroes, we will find only conflated versions of mythic, larger-than-life idols. The true heroes are among us, and we must see them for who they are--"essential men", ordinary people.

I agree with Aurora Leigh. There are heroes within our lives, whether we know them personally or view them from afar. These people are so much more real than the epic heroes we read of in history books or see in movies. These real people are not always famous enough to be recorded in the volumes of history, but such idolatry is not necessary is the making of a hero.

Wednesday, March 18, 2009

Guest Speaker Bess Calhoun, "Aurora Leigh"

Background

Elizabeth Barrett Browning was one of twelve children, and her father forbade his children to marry. She was bedridden for most of her life (due to her nervous condition) until she eloped with Robert Browning, whom she met through an ongoing letter-correspondence.

Close-reading, Book II, 671-684

1. Aurora defends her choice by saying that she would be lying if she said "yes" to marrying Romney, and that it is God's will that she refuse his proposal. She also declares that she doesn't need money to nourish her soul; and marriage, in providing that monetary stability, is not necessarily important to her.

2. Aurora's use of God in this passage shows that it is not just her personal decision to refuse Romney; God has compelled her to do so. This thus gives her argument more weight and justifies her determination to tell the truth.

3. Aurora differentiates between her "soul's life" and her monetary life by saying "My soul is not a pauper; I can live/At least my soul's life, without alms from men" (681-682). Clearly, Aurora feels strongly about the nourishment of her soul and does not think that a monetary will allow for the growth and freedom of her soul. This also shows her desire to be independent from the financial contract offered by Romney, a contract which would not permit her to pursue the life (of poetry) that will feed her soul.

4. Aurora and her aunt have very differing notions of femininity. Aurora gravitates towards the wild femininity she perceives as the persona embodied by her Italian mother. Aurora's aunt declares that "You cannot eat or drink or stand or sit/Or even die...Without your cousin" (658-661). Obviously, she does not think Aurora can survive without Romney. She views Aurora's marriage to Romney as the epitome of femininity, while Aurora sees such an arrangement as severely limiting to her notion of independent femininity.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning was one of twelve children, and her father forbade his children to marry. She was bedridden for most of her life (due to her nervous condition) until she eloped with Robert Browning, whom she met through an ongoing letter-correspondence.

Close-reading, Book II, 671-684

1. Aurora defends her choice by saying that she would be lying if she said "yes" to marrying Romney, and that it is God's will that she refuse his proposal. She also declares that she doesn't need money to nourish her soul; and marriage, in providing that monetary stability, is not necessarily important to her.

2. Aurora's use of God in this passage shows that it is not just her personal decision to refuse Romney; God has compelled her to do so. This thus gives her argument more weight and justifies her determination to tell the truth.

3. Aurora differentiates between her "soul's life" and her monetary life by saying "My soul is not a pauper; I can live/At least my soul's life, without alms from men" (681-682). Clearly, Aurora feels strongly about the nourishment of her soul and does not think that a monetary will allow for the growth and freedom of her soul. This also shows her desire to be independent from the financial contract offered by Romney, a contract which would not permit her to pursue the life (of poetry) that will feed her soul.

4. Aurora and her aunt have very differing notions of femininity. Aurora gravitates towards the wild femininity she perceives as the persona embodied by her Italian mother. Aurora's aunt declares that "You cannot eat or drink or stand or sit/Or even die...Without your cousin" (658-661). Obviously, she does not think Aurora can survive without Romney. She views Aurora's marriage to Romney as the epitome of femininity, while Aurora sees such an arrangement as severely limiting to her notion of independent femininity.

Monday, March 16, 2009

Notes 3/16: Aurora Leigh

Aurora Leigh...the third great epic poem? It is a growth story, a coming of age story--about a female poet.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning:

She published her first book of poetry when she was 22. She was so famous as a poet, that they considered making her Poet Laureate. Her father cloistered her; she became an invalid and developed a dependence on morphine. In 1845, she met Robert Browning (through a letter) and they kept up a secret correspondence. She and Robert eloped, lived in Italy, and were very radical in their beliefs and lifestyles. She and Robert loved each other to the end of her life, 15 years after they met.

Elizabeth's life is very different from the beginning of Aurora Leigh's life:

After her mother and father die, Aurora goes to live with her aunt (her father's sister). She differentiates between living in a worldly, "living and breathing" sense and living in a spiritual, more "real" sense. Aurora's father is older when he meets her mother in Italy. He is made uncommon, but doesn't take a step forward to cultivate his genius. When his wife dies, Aurora's father is totally bereft, and refocuses his love upon Aurora.

*What shapes our minds and makes us who we are?

We're shaped by our parents, the media, what we read, who we interact with, music. and everything around us...EBB is exploring this idea in her poem.

First Book:

Elizabeth Barrett Browning:

She published her first book of poetry when she was 22. She was so famous as a poet, that they considered making her Poet Laureate. Her father cloistered her; she became an invalid and developed a dependence on morphine. In 1845, she met Robert Browning (through a letter) and they kept up a secret correspondence. She and Robert eloped, lived in Italy, and were very radical in their beliefs and lifestyles. She and Robert loved each other to the end of her life, 15 years after they met.

Elizabeth's life is very different from the beginning of Aurora Leigh's life:

After her mother and father die, Aurora goes to live with her aunt (her father's sister). She differentiates between living in a worldly, "living and breathing" sense and living in a spiritual, more "real" sense. Aurora's father is older when he meets her mother in Italy. He is made uncommon, but doesn't take a step forward to cultivate his genius. When his wife dies, Aurora's father is totally bereft, and refocuses his love upon Aurora.

*What shapes our minds and makes us who we are?

We're shaped by our parents, the media, what we read, who we interact with, music. and everything around us...EBB is exploring this idea in her poem.

First Book:

"I have not so far left the coasts of lifeIn these early lines, Aurora is talking about becoming acculturated, and that fact that infants can sense the divine and the infinite because they have not yet been shaped by culture. At this point in the poem, Aurora refers to her mother's understanding of such divine moments. In fact, her mother "could not bear the joy of giving life/The mother's rapture slew her" (34-35). Her mother was quite adoring, like Victor's mother, and Aurora searches for her mother's deep, unconditional love after her death. Aurora compares a mother's love to a father's love, saying that women know how to raise children, and have a way of making children feel completely loved. Every word a mother says to her children is meaningful, and she in turns understands every attempted word her child utters. This is how children are brought into language, acculturated into civilization. These words that a child learns tell her how to view the world, how to feel about the world. But instead of just saying that words are cutting (like knives), she instead says that words are beautiful, like corals.

To travel inland, that I cannot hear

That murmur of the outer Infinite

Which unweaned babies smile at in their sleep

When wondered at for smiling" (lines 10-14).

Aurora Leigh, Book I

Describe Aurora:

In her first book, Aurora is a young girl, describing her life from birth up to her teenage years. She is obviously a very sensitive and perceptive girl, aware of how her mother's death would have affected her father and how his child-rearing skills were put to the test. Aurora marks her father's death as the end of her childhood; it is at this time that she goes to live with her brother's older sister. Aurora is extremely conscious of her new surroundings and of her new housemate. She sees her aunt as her complete opposite; Aurora, a wild and free fledgling, stands in stark contrast to the aunt who lives a caged-bird life. Aurora is thus keenly aware of the differences between herself and her aunt, and I think this propels her on her path of self-discovery. As she pores through various books, she discovers poetry--and Aurora, intuitive child that she is, is convinced that it is her own poetry-writing that pulls her back from despair and restores her to life.

Friday, March 6, 2009

Notes 3/6: The Lifted Veil, Ch. II

"Low spirits! That is the sort of phrase with which coarse, narrow natures like ours think to describe experience of which you can know no more than your horse know" (Latimer contemplating his brother Alfred, p.28). Latimer is assuming that he alone suffers, and that Alfred can never understand him because he believes that Alfred has absolutely no doubts, no fears. This perhaps is evidence that Latimer cannot read Alfred's mind--if he could read his mind, he would inevitably find at least some feelings of doubt. Latimer doesn't really even seem to know his brother at all, and Latimer wants nothing to do with him. There has to be something more to Alfred than Latimer thinks he knows; Latimer can't even predict his brother's death, predicting instead that he would only be prevented from Bertha if he found a better woman.

Bertha's marriage philosophy is very cynical. She says that loving the person you marry is problematic because you will always be jealous and it is much more elegant to marry someone you don't care about. When Bertha says this, Latimer tells her "Bertha, that is not your real feeling. Why do you delight in trying to deceive me by inventing such cynical speeches?" (6). Latimer is easily deceived because he already spends so much tome inviting his own ideas and placing them onto others.

Here's a theory: Latimer is not clairvoyant, he can't tell what people think. Instead, he is just really good at projecting his own thoughts and feelings upon others. It may be impossible not to project on someone you really love. Perhaps you need that assurance that that person is who you think. But then do you love the person or what you have made of the person? In Latimer's case, it seems that Latimer does not love Bertha for who she is (a cynical girl who does not care about him) but instead he loves the Bertha he has made through his projections--he absolutely adores his creation. Later, when he no longer loves Bertha, he projects different feelings onto her--demonizing feelings of hatred and disgust.

Wednesday, March 4, 2009

Interior Thoughts...and The Lifted Veil

picture of women on couch (and her stream of consciousness):

I wonder how this dress makes me look. I hope it doesn't show any of the gross side bulge I've been going to the gym to get rid of because those workouts are hard, excruciating actually, yes but they are worth it, I'm not fat, I have no bulges, I am beautiful I am beautiful Am I beautiful? Tell me I'm beautiful.

Can Latimer read people's minds, or is he doing what we all do (in assuming what people say)??

Latimer is perhaps just extremely imaginative and able to come up with people's "thoughts" by their body language and facial cues. Latimer, of course, unquestioningly believes in the accuracy and authenticity of his visions. Evidence for such power comes from his vision of Prague and his subsequent visit to the city (where he confirmed his belief). He also guessed his brother's speech before he made it, and saw the vision of Bertha before he met her. And yet, Latimer could just have easily seen a painting of Prague, for example.

But why can't Latimer read Bertha's mind?

Knowing what Bertha was thinking would take the fun out of the romance (at least for Latimer). He can instead project his own desires and thoughts onto Bertha; she becomes what he wants her to be. He sees her as pretending to love Alfred while she secretly loves Latimer. Latimer craves her love; he worships her. The hold that Bertha has over him comes from the tyrannical power she has over him.He sees her as having a deeply cynical soul, and that something is going to move her--and it is going to be him. Obtaining Bertha's love would be like winning a colossal struggle.

Perhaps this strong desire for Bertha comes from the distance that has been established between Latimer and his late mother.

How does Latimer feel about himself?

He thinks he is an amazing person: "I am cursed with an exceptional mental character" (7). Clearly, Latimer feel himself to be governed by a fate that has been set before him, a fate this governed by his own intellect. He regards himself as an emotional poet in that he does not write, but has the same sensibilities as a poet. He doesn't trust anyone else; he feels alone and confined to his own wretched misery.

I wonder how this dress makes me look. I hope it doesn't show any of the gross side bulge I've been going to the gym to get rid of because those workouts are hard, excruciating actually, yes but they are worth it, I'm not fat, I have no bulges, I am beautiful I am beautiful Am I beautiful? Tell me I'm beautiful.

Can Latimer read people's minds, or is he doing what we all do (in assuming what people say)??

Latimer is perhaps just extremely imaginative and able to come up with people's "thoughts" by their body language and facial cues. Latimer, of course, unquestioningly believes in the accuracy and authenticity of his visions. Evidence for such power comes from his vision of Prague and his subsequent visit to the city (where he confirmed his belief). He also guessed his brother's speech before he made it, and saw the vision of Bertha before he met her. And yet, Latimer could just have easily seen a painting of Prague, for example.

But why can't Latimer read Bertha's mind?

Knowing what Bertha was thinking would take the fun out of the romance (at least for Latimer). He can instead project his own desires and thoughts onto Bertha; she becomes what he wants her to be. He sees her as pretending to love Alfred while she secretly loves Latimer. Latimer craves her love; he worships her. The hold that Bertha has over him comes from the tyrannical power she has over him.He sees her as having a deeply cynical soul, and that something is going to move her--and it is going to be him. Obtaining Bertha's love would be like winning a colossal struggle.

Perhaps this strong desire for Bertha comes from the distance that has been established between Latimer and his late mother.

How does Latimer feel about himself?

He thinks he is an amazing person: "I am cursed with an exceptional mental character" (7). Clearly, Latimer feel himself to be governed by a fate that has been set before him, a fate this governed by his own intellect. He regards himself as an emotional poet in that he does not write, but has the same sensibilities as a poet. He doesn't trust anyone else; he feels alone and confined to his own wretched misery.

Like Latimer, Like Victor

Does Latimer resemble Victor?

Poor Latimer, poor Victor: I think that Latimer definitely resembles Victor in the way that he suffers terribly. The difference comes from the origin of their suffering--for Victor, it is self-inflicted, while Latimer cannot control his ability to see into people's souls. Nonetheless, the two men share similar childhoods--both were brought up without financial restrictions upon their various travel and educational opportunities, and both were deeply affected by the loss of a mother. The pain that he man has gone through is elevated to the point that each desires the welcome escape offered by death. Another interesting resemblance between these two men is the use of the word "wretched" to describe their characters and situations. Latimer considers his clairvoyant knowledge to be "wretched" and sees the end of his life as being in a constant state of "wretchedness" (20, 36). Clearly, Victor and Latimer are figures whose lives have been wracked with, and will never be free from, torment.

Poor Latimer, poor Victor: I think that Latimer definitely resembles Victor in the way that he suffers terribly. The difference comes from the origin of their suffering--for Victor, it is self-inflicted, while Latimer cannot control his ability to see into people's souls. Nonetheless, the two men share similar childhoods--both were brought up without financial restrictions upon their various travel and educational opportunities, and both were deeply affected by the loss of a mother. The pain that he man has gone through is elevated to the point that each desires the welcome escape offered by death. Another interesting resemblance between these two men is the use of the word "wretched" to describe their characters and situations. Latimer considers his clairvoyant knowledge to be "wretched" and sees the end of his life as being in a constant state of "wretchedness" (20, 36). Clearly, Victor and Latimer are figures whose lives have been wracked with, and will never be free from, torment.

Monday, March 2, 2009

Hero Machine Experiment

"Clerval the Caretaker"

I decided to make "Clerval the Caretaker." He is a loyal and faithful friend to Victor, and is always ready to support him in his worst moments. Since Clerval is an ever-ready caretaker for Victor, I have depicted him as a concerned, nurse-like figure. Covering his right hand is a yellow glove, symbolic of the type of sanitary attire a nurse might wear. On his other hand rests a snake, the animal figure associated with medicine. The cross around his neck is representative of the selfless love that Clerval gives to Victor, and the sacrifices he makes to ensure his friend's well-being. The sword across Clerval's back emphasizes his readiness to to defend and take care of Victor. Finally, the leaves in the background show the sense of peace that accompanies Clerval; Victor regards him as a comforting aspect of his life, as calming as the Spring-like leaves that surround him.

End of Frankenstein:

At the end of the novel, Victor is adamant that Walton should not increase his own miseries by following the path the Victor took. And at the same time, Victor is contradictory in that he tries to persuade the men into heroic sacrifice. He is able to recognize his own past mistakes, but he does not seem able to fully understand his mistakes to the point that he does not repeat them; he even encourages others to sacrifice their lives and loved ones just as he did.

Is this full blown heroism? Perhaps Victor is a hero; and that the desires that motivate heroism are NOT heroic. Maybe the secret behind heroism is that it is a way to escape intimacy and vulnerability with those whom you love.

Friday, February 27, 2009

Notes, up to page 153

The Monster threatens Victor: "I will be with you on your wedding night!" Victor automatically assumes that the Monster is going to kill him, not another of his loved ones. The Monster doesn't want to kill Victor because...

...he cannot bring himself to kill his Creator

...he wants to make Victor suffer

...he wants to teach Victor a lesson, so that maybe he will change his mind...they are the same person (Maybe there is no monster; maybe they are one and the same)

*Research question: Are Victor and the Monster one and the same person?

The biggest argument against this is the question of why Victor would want to kill his friends and family. But perhaps Victor is sheerly self-destructive; maybe he is trying to get rid of these people before they can hurt him. He wants to make sure that he will not be as hurt as he was by his mother's death.

so if they are the same person, who does the term "the wretch" refer to?

-on page 119, Victor calls himself a "miserable wretch" as he and Clerval begin their journey

-on page 131, the Monster threatens Victor for destroying the female creation: "I can make you so wretched that the light of day will be hateful to you" Clearly, Victor feels as wretched as the Monster does.

-After Victor is thrown into prison, he describes himself as "wretched" and "a wretch" several times. His despondency is encompassed in the repetition of the word "wretch," and he is once again relating himself to the only other wretch in the story--the Monster.

-When Victor and his father are returning to Geneva, Victor confesses: Human beings, their feelings and passions, would indeed be degraded if such a wretch as I felt pride" (145). Victor fancies himself to be a wretch and a murderer--something his father clearly does not believe. He says that he killed Justine; the Monster is enacting his wishes (in accordance with the idea that they are the same person).

Even if they are not the same person, they are definitely in a mirroring relationship. Is Victor inflecting wretchedness upon himself? If he can't be the best, perhaps he wants to be the worst. (like Satan's fall). Why would Victor want to live so wretchedly? Perhaps it is part of his belief that others can hurt him, and he is trying to protect himself from such suffering.

-After Victor is thrown into prison, he describes himself as "wretched" and "a wretch" several times. His despondency is encompassed in the repetition of the word "wretch," and he is once again relating himself to the only other wretch in the story--the Monster.

-When Victor and his father are returning to Geneva, Victor confesses: Human beings, their feelings and passions, would indeed be degraded if such a wretch as I felt pride" (145). Victor fancies himself to be a wretch and a murderer--something his father clearly does not believe. He says that he killed Justine; the Monster is enacting his wishes (in accordance with the idea that they are the same person).

Even if they are not the same person, they are definitely in a mirroring relationship. Is Victor inflecting wretchedness upon himself? If he can't be the best, perhaps he wants to be the worst. (like Satan's fall). Why would Victor want to live so wretchedly? Perhaps it is part of his belief that others can hurt him, and he is trying to protect himself from such suffering.

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

Notes 2/25: Frankenstein up to Vol. III

Here's a (newish) idea: If you bring up children properly, you will create a better world. Should we let children learn things on their own so that they will not be swayed by prejudices/judgments? There was an experiment done in which a man adopted two children and told them NOTHING. This was taking it a bit too far, and the children became deeply disturbed (they were not told, for example, about the dangers of fire). Thinkers like William Godwin (Mary Shelley's father) said that people learn from what they see; in the Reign of Terror, for example, the peasants had learned from the aristocrats that rulers are supposed to be brutal.

Comparing the Monster to a child:

The Monster is like a neglected child, who has never been taught anything, has never been shown any affection, and is confused about his place in the world. Victor completely abandons his Monster; the neglect thus turns his creation into a monster. This goes along with the idea that your upbringing goes a long way in shaping who you are. But at some level, there is some sort of moral choice. The Monster's behavior, for example, reflects his upbringing of neglect as well as the moral choices that he makes on his own. An example of such a moral choice would be when he framed Justine for the murder.

There is a sense of accomplishment that goes into raising "good" children. Parents can do the same things for their children but have different motives--it depends on whether or not they are looking for happiness for their children or pride for themselves. Parents can put such pressure upon their children to do well that they choose instead to rebel.

The Monster, feeling Victor's neglect, seems as if he will do anything to get his attention--even if it is negative attention. This occurs when he murders William: "You belong to my enemy--to him towards whom I have sworn eternal revenge; you shall be my first victim" (109). Although the Monster does want to kill William at this point, it was not his original intent to do so. The Monster at first was good, and at first looked to William for companionship. Because he cannot have the comfort of companionship, the Monster blames Victor for his unhappiness; he believes Victor owes him happiness.

Tuesday, February 24, 2009

Frankestein, end of Vol. II

How does the Monster's tale make you feel about him?

After reading the monster's tale, I just felt so terribly sorry him. I saw how he began his life as a lonely creature, unsure of what to make of the world and how to function in it. Once he understood that he was different from the humans he encountered, he was determined to learn as much as he could in order to draw upon their compassion. I respected the Monster for his determination; even after the first villagers chased him, he believed in the ultimate good of human nature. He realizes that he has no relations, that he is missing the companionship that the only man and his children have. He sadly questions his own situation: "But where were my friends and relations? No father had watched my infant days, no mother had blessed me with smiles and caresses" (91). This sense of a lost family is what drives the Monster to seek Victor; he needs someone with whom he can share his life. The Monster's innate need for love is something that I can relate to--it is a basic human emotion that everyone can understand. Thus, I feel sorry for the Monster because he has tried so hard with the family in Germany, and must now resort to begging his creator to make a mate for him.

After reading the monster's tale, I just felt so terribly sorry him. I saw how he began his life as a lonely creature, unsure of what to make of the world and how to function in it. Once he understood that he was different from the humans he encountered, he was determined to learn as much as he could in order to draw upon their compassion. I respected the Monster for his determination; even after the first villagers chased him, he believed in the ultimate good of human nature. He realizes that he has no relations, that he is missing the companionship that the only man and his children have. He sadly questions his own situation: "But where were my friends and relations? No father had watched my infant days, no mother had blessed me with smiles and caresses" (91). This sense of a lost family is what drives the Monster to seek Victor; he needs someone with whom he can share his life. The Monster's innate need for love is something that I can relate to--it is a basic human emotion that everyone can understand. Thus, I feel sorry for the Monster because he has tried so hard with the family in Germany, and must now resort to begging his creator to make a mate for him.

Monday, February 23, 2009

Notes 2/23 Frankstein up to Vol. II, Ch. III

*The closer you are to someone, the more that that person can hurt you. For example, Victor so intensely loves his mother that he is deeply wounded by her death.

The poems/stories alluded to in Frankenstein:

The story of Prometheus: He gave fire to humankind. In punishment for bestowing such a powerful tool upon humans, Prometheus is chained to a mountaintop. Victor is the "modern Prometheus" because he is trying to give immortality to humans, and he will be punished accordingly.

"Rime of the Ancient Mariner": An old man tells a young wedding guest his story. His story is about this ship where an albatross flies everyday and the mariners feed it and love it. The ancient Mariner shoots this albatross, however, and calamities befall the men. They are so mad at him that they hang the albatross around his neck. The mariner realizes that he has "slimy things" inside himself and around him. In the moonlight, however, he sees the beauty in the "slimy things" and the albatross falls from his neck. The bird is a Christ-like image, who loved the mariner unconditionally. This intense love is what drives the mariner to kill the albatross. Why the crucifixion? Deep, unconditional love is really quite scary, and killing that potential love prevents the terrible fear and anxiety caused by the suffering of losing them. If you push it away first, you save yourself the heartbreak. (at least, this is the idea).

...similar message in "Alastor": In lines 129-139, the narrator (a poet) tells of a young Arab maiden he meets and later dreams about. In his dream, she is is soulmate and is about to throw herself into his arms when he wakes up. He is thus haunted and searches the world for his lost vision of love. The poet has spurned her choicest gifts; he did not want to get involved with someone who could hurt him and disappoint him. Instead, he choices the image of ideal love instead of resigning himself to real love.

Do either of these characters resemble Victor?

Well, Victor spurns nature's choicest gifts when he is in the process of creation. Simply pursuing that goal pits him against nature. Additionally, he goes through a period in which he can no longer find joy in the simple aspects of nature. He doesn't pursue relationships while in the workshop of creation. He stops writing to his father and cuts off contact with Elizabeth. Why? He is attempting to prevent Elizabeth from hurting him; he is making sure that he will not be living in a world without her.

"It was on a dreary night of November..." Victor has successfully brought his creation to life, and is overcome with horror at what he has done. He falls into the bed, and dreams a terrifying dream in which he sees Elizabeth dying and transformed into his own dead mother. He wakens with a start and sees the monster, who is trying to contact him. Victor leaps out of bed, locks up the apartment and stays outside because he never wants to see his monster again. Clerval becomes his nurse and attends to his psychotic hallucinations. Thanks to Clerval's care, Victor recovers: "In a short time I became as cheerful as before I was attacked by the fatal passion" (41). Here, Victor is once again blaming fate and its uncontrollable role within his life. Victor passively attests to being under the attack of fate. Victor is not owning up to the fact that he indulged in passion and does not take the blame for his actions. This inability to confess to his mistakes is seen again when he does not stand up to defend Justine. At this point, he has just given up and is completely controlled by his acceptance of fate.

Victor compares himself to Satan by quoting Milton's Paradise Lost: "I bore a hell within me" (64). Victor believes himself to suffer more than anyone else, and takes no notice of the fact that Elizabeth is in so much pain that she wishes to die along with Justine. This reflects Victor's ever-present desire to be the greatest--at this point, at least, he believes himself to be the greatest sufferer.

The poems/stories alluded to in Frankenstein:

The story of Prometheus: He gave fire to humankind. In punishment for bestowing such a powerful tool upon humans, Prometheus is chained to a mountaintop. Victor is the "modern Prometheus" because he is trying to give immortality to humans, and he will be punished accordingly.

"Rime of the Ancient Mariner": An old man tells a young wedding guest his story. His story is about this ship where an albatross flies everyday and the mariners feed it and love it. The ancient Mariner shoots this albatross, however, and calamities befall the men. They are so mad at him that they hang the albatross around his neck. The mariner realizes that he has "slimy things" inside himself and around him. In the moonlight, however, he sees the beauty in the "slimy things" and the albatross falls from his neck. The bird is a Christ-like image, who loved the mariner unconditionally. This intense love is what drives the mariner to kill the albatross. Why the crucifixion? Deep, unconditional love is really quite scary, and killing that potential love prevents the terrible fear and anxiety caused by the suffering of losing them. If you push it away first, you save yourself the heartbreak. (at least, this is the idea).

...similar message in "Alastor": In lines 129-139, the narrator (a poet) tells of a young Arab maiden he meets and later dreams about. In his dream, she is is soulmate and is about to throw herself into his arms when he wakes up. He is thus haunted and searches the world for his lost vision of love. The poet has spurned her choicest gifts; he did not want to get involved with someone who could hurt him and disappoint him. Instead, he choices the image of ideal love instead of resigning himself to real love.

Do either of these characters resemble Victor?

Well, Victor spurns nature's choicest gifts when he is in the process of creation. Simply pursuing that goal pits him against nature. Additionally, he goes through a period in which he can no longer find joy in the simple aspects of nature. He doesn't pursue relationships while in the workshop of creation. He stops writing to his father and cuts off contact with Elizabeth. Why? He is attempting to prevent Elizabeth from hurting him; he is making sure that he will not be living in a world without her.

"It was on a dreary night of November..." Victor has successfully brought his creation to life, and is overcome with horror at what he has done. He falls into the bed, and dreams a terrifying dream in which he sees Elizabeth dying and transformed into his own dead mother. He wakens with a start and sees the monster, who is trying to contact him. Victor leaps out of bed, locks up the apartment and stays outside because he never wants to see his monster again. Clerval becomes his nurse and attends to his psychotic hallucinations. Thanks to Clerval's care, Victor recovers: "In a short time I became as cheerful as before I was attacked by the fatal passion" (41). Here, Victor is once again blaming fate and its uncontrollable role within his life. Victor passively attests to being under the attack of fate. Victor is not owning up to the fact that he indulged in passion and does not take the blame for his actions. This inability to confess to his mistakes is seen again when he does not stand up to defend Justine. At this point, he has just given up and is completely controlled by his acceptance of fate.

Victor compares himself to Satan by quoting Milton's Paradise Lost: "I bore a hell within me" (64). Victor believes himself to suffer more than anyone else, and takes no notice of the fact that Elizabeth is in so much pain that she wishes to die along with Justine. This reflects Victor's ever-present desire to be the greatest--at this point, at least, he believes himself to be the greatest sufferer.

Sunday, February 22, 2009

Walton vs Victor

How is Victor like/unlike Walton?

As supposed by Victor, he and Walton do share the same madness. Each man is seeking to carve his name into the history books--to achieve fame that is everlasting. The difference between the two men is that Walton is seeking a fame that, once achieved, commands respect only from those who are aware of such "conquest" expeditions. Victor, however, seeks to forever be emulated by his creation. Victor will not only command everyone's respect for being the first to create life, but he will be directly in control of the "creature" he has brought to life. Thus, Victor seeks the adoring, grateful devotion of the thing he has created. This goes even a step further than simply securing a spot for himself in the history books; Victor is actually making sure that his name will live on and be worshiped by the creature upon whom he has so kindly bestowed the gift of life. Aside from the sheer fame that Walton seeks, Victor wants unadulterated gratitude and adoration. This is made clear in Victor's description of his hopes for his creation: "A new species would bless me as its creator and source; many happy and excellent natures would owe their being to me" (34). Obviously, Victor is searching for a feeling of total ownership; he wants an entire species to be dependent upon his superior abilities of creation. This different from Walton, whose quest for fame is not oriented upon a relationship of control.